James Lecture: Scholar Alda Benjamen to discuss how Assyrians gained agency in an often-overlooked period of modern Iraqi history

March 15, 2024

In her April 10 event at the Guild Lounge, Benjamen will discuss how Assyrians, long marginalized and minoritized in Iraq, gained agency in an often-overlooked period of modern Iraqi history.

Spanning thousands of years, the history of the Assyrian people is undoubtedly rich and layered.

The Assyrians, whose roots exist in Mesopotamia, or modern-day Iraq, Iran, Turkey, and Syria, are the last speakers of Aramaic, a now-endangered ancient language that was once the lingua franca of the Middle East. They adopted Christianity in their early years, founding the Syriac faith and liturgy.

Assyrians preserved linguistic, cultural, and religious traditions steeped in their Mesopotamian heritage and passed them onto future generations in tangible and intangible formats. While contributing to various civilizations, including Islamic and Ottoman, and co-existing with other communities, the Assyrians also faced oppression and marginalization, especially during the modern periods of the nation-state formation and into the current-day Islamic State.

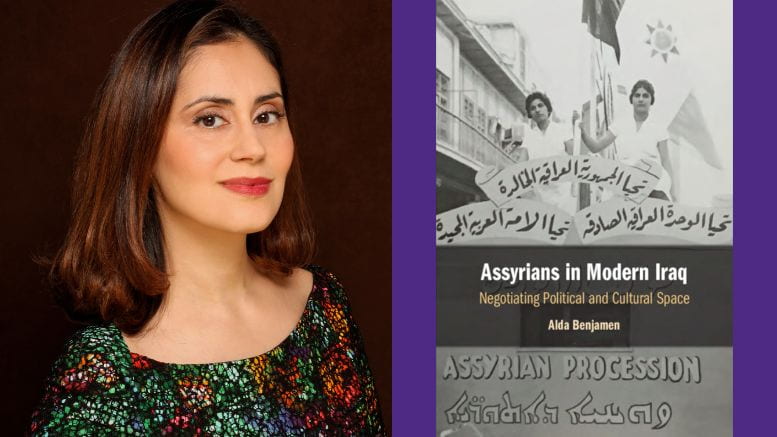

Alda Benjamen, an assistant professor of history at the University of Dayton, is part of a burgeoning scholarly community examining Assyrian history and culture, particularly in contemporary times.

The first U.S. scholar to use Iraqi archives in Baghdad after the 2003 fall of Saddam Hussein, Benjamen’s 2022 book, Assyrians in Modern Iraq: Negotiating Political and Cultural Space, leans into archival research as well as oral and ethnographic sources to paint a detailed portrait of Assyrian life in Iraq between the British monarchy’s rule and Hussein’s authoritarian regime.

Michael Rakowitz, the Alice Welsh Skilling Professor of Art in Northwestern University’s Department of Art Theory and Practice, often touches on Iraqi history in his own work and says he cannot “throw enough superlatives at Dr. Benjamen’s work” detailing modern Assyrian history in Iraq.

“Dr. Benjamen’s work is so important because it doesn’t locate Assyrian people in antiquity, as is so often the case, but rather highlights how the Assyrian community is central to Iraq’s modern history,” says Rakowitz, who is also a core faculty member in Northwestern’s Middle East and North African Studies Program.

On April 10, Benjamen will visit Northwestern’s Evanston campus to deliver the Jeremiah S. and Helen James Lecture at the Guild Lounge. Spurred by the philanthropy of the late couple, both of whom were Assyrian immigrants to the United States, the annual James Lecture promotes understanding and scholarship of ancient and modern Assyrian culture.

Benjamen discusses her upcoming visit to Northwestern and her study of an often overlooked, yet transformative period for many in Iraq’s marginalized Assyrian community.

What will you cover in your James Lecture on April 10?

My talk, like my book, will explore Assyrians in the modern period of Iraq, the 1960s to the 1980s. This 20-year period is a time of change for the region as a whole and we see a lot of Assyrian migration, particularly rural-urban migration to cities like Baghdad for employment opportunities. I’ll talk about my research methodology, which is important to note when you’re dealing with a minoritized community, and also discuss the pluralistic spaces Assyrians engage in during this time.

Let me add, I’m excited to give this talk in the Chicago area, which is home to one of the world’s largest Assyrian communities. I hope members of the local Assyrian community can join us to gather more historical context and cultural understanding about a time not so long ago.

Why is this 20-year window in the latter half of the 20th century a notable time for Assyrians in Iraq?

This is a period in which Assyrians emerge from the periphery of society and begin to engage with wider intellectual and political movements across Iraq. They’re able to lose, even if temporarily, their minoritized, marginalized status and they find room to form strategic alliances to maneuver and advance issues beneficial to Assyrian community at large. They gain cultural rights and standardize their language across the various Eastern Aramaic dialects, publishing important works and leading to a cultural renaissance, while also contributing in Arabic to Iraq’s hierarchical but pluralistic intellectual space.

It’s also worth mentioning that there’s very little about this period in Iraqi history. There’s a lot on the British monarchy that lasted into 1958 – British sources, after all, were easily accessible to scholars when they couldn’t travel to Iraq – but then there’s a lull in interest until the 1980s and the war with Iran followed by the U.S. invasion. Still, this is a foundational period in Iraqi history. Many of the policies and negotiations the Assyrian community engages with are developed during this time. We see how the international community interacts with the Iraqi state as well as what the state values, what it tokenizes, and how it deals with its minoritized communities.

Having studied this period extensively, what do you find personally fascinating about this era in Iraq?

When we think of Iraq, we tend to think of the authoritarian system of Saddam Hussein and the complete absence of rights for Assyrians and many Iraqis, much of which is true, of course. The period I cover, though, shows that any government goes through phases. The phase I investigate shows that the Assyrian people have agency and – although it’s relative and they know it’s something they must negotiate and be careful with – they are nevertheless pushing the system and engaging with it, at least until the war with Iran starts in 1980 and the government becomes more repressive. Things change then because a regime can hide a lot under the umbrella of war.

Why is it relevant to look at this period in Iraqi history right now?

When we look at modern Iraq, in particular, the focus is often on the politicized aspects of the country – international engagement with the war in Iraq or the rise of Saddam Hussein, for instance. Yet, such a narrow focus is problematic. It ignores this important period showing spaces for state-society negotiations and communities coming together strategically to form alliances. This is a time of pluralistic intellectual engagements that proves more inclusive and empowering.

Simultaneously, we also see how international actors influence the state and how the state negotiates with minorities. The question is: are we really serious about pluralistically thinking about our communities and giving agency to everyone and a healthy co-existence or are we tokenizing these communities to get some policy thing moving forward? And today, I think history is repeating itself in many ways and we need to be honest about what’s taking place.

What do you hope the audience takes away from your program?

First, I hope people gain a deeper understanding of this period’s background, a transitional period their parents or grandparents might have lived through, and how Assyrians became actively involved in intellectual and social engagements of the time. My work involved a lot of oral interviews with individuals in Iraq and actually Chicago community members who were significant actors in this movement before having to leave the country. I hope it drives appreciation for the lives of those Assyrians who engaged during this time and helps us understand where they’re coming from.

Second, I hope my talk underscores the need to preserve the modern history of the Assyrian community. With the continuous displacement, especially since the genocidal campaigns against minorities in Iraq, communities who lived in the north have seen a lot of their heritage destroyed. These cultural elements are extremely valuable and we need to preserve their heritage, the tangible as well as the intangible.

Is preservation actively happening now?

Fortunately, yes. I’m working on a project now with the support of USAID funding that includes partnering with local organizations to digitize their heritage – songs, texts, manuscripts, and the like in Iraq. We need to engage in similar efforts in the diaspora and especially in the Chicagoland area, where such a large community exists and owns rich heritage of relevance not only to their own community but also that of Middle Eastern history.

There is an exciting rise in scholarship dealing with minorities in the Middle East. Increasingly, we’re looking at them not through minoritization only, but rather pluralistic engagements giving them agency. We’re not thinking of them as fifth columns in their societies, but instead thinking of them as contributors important to the broader community, which is a wonderful turn.

Society & Policy

Joel Mokyr wins Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences

October 13, 2025

Nobel recognizes Mokyr’s theory on sustained economic growth Joel Mokyr, the Robert H. Strotz Professor of Arts and Sciences and professor of economics and history in the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences at Northwestern University, today (Oct….

Weinberg College faculty and graduate students recognized for excellence in teaching

July 2, 2025

Each year, the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences and the Office of the Provost recognizes members of the College’s tenure-line and teaching-track faculty for excellence in teaching. Weinberg College in addition recognizes the contributions…

Passion for the planet: A new generation of environmental stewards starts here

May 29, 2025

Over the last two decades, the Weinberg College-housed Program in Environmental Policy and Culture (EPC) at Northwestern has embraced the humanities and social sciences and cultivated a new generation of environmental stewards. Growing up in…

The real beneficiaries of protective labor laws for women

May 20, 2025

During the first half of the 20th century, many states passed labor laws in response to the influx of women into the modern workplace. The so-called protective labor laws enacted by U.S. states restricted women’s…